Like many black boxers in the 1920s, a post-Jack Johnson landscape left Harry Wills with very little prospect in the world of prizefighting.

Johnson’s supposedly arrogant demeanour, and open relationships with white women, as heavyweight champion of the world between 1908 and 1915, at the height of the Jim Crow era, outraged white America so much that after he lost the title to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba, it left little opportunity for another black fighter to challenge for the title for a very long time.

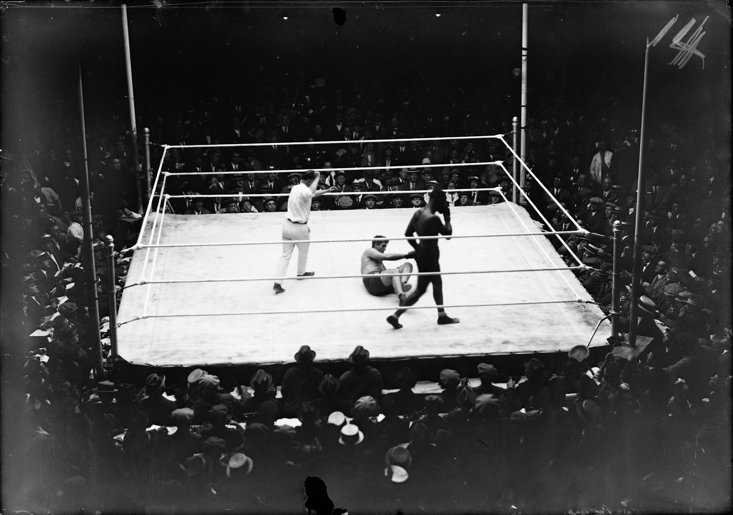

Wills, who entered the ring as ‘the Black Panther,’ was a victim of the time in which he was born and the fact that one of the most supremely-talented heavyweights in the history of the sport was unable to fight for the world title purely based on the colour of his skin is criminal.

Born in New Orleans in 1889, Wills is considered by many boxing historians as the biggest victim of the colour line drawn by white boxing champions in the early 20th Century. In a career spanning over 20 years between 1911 and 1932, Wills fought many of the best heavyweights around at the time but was at the same time massively hamstrung in who he could fight, often pitted against the other black heavyweights of the era, similarly lacking wider opportunity.

Sam Langford, another brilliant heavyweight who’s potential would never be realised, fought Wills a stunning 22 times, with both boxers picking up the World Coloured Heavyweight Championship twice each against one another.

Alongside Wills and Langford were Sam McVey and Joe Jeanette, another two exceptional black heavyweights who could have undoubtedly beaten any man on the planet on their day, regardless of skin colour, but were never given their shot.

That wasn’t to say Wills didn’t mix it with some of the best white boxers of the time too, albeit never for a world title, stopping Gunboat Smith inside just a round, earning a decision over ‘The Wild Bull of Pampas’ Luis Firpo, who’d previously given Jack Dempsey a big scare, and beating Willie Meehan, who’d triumphed over Dempsey twice.

With sledgehammer-fists and a huge 6ft 4ins frame cast into steel from working long hours as a longshoreman in the ‘Big Easy’, Wills’ best asset was, unsurprisingly, his terrifying power. Out of his 75 professional victories, 47 were finished by way of knockout, a feat recognised by The Ring magazine in 2003, when they included him in their list of the 100 hardest punchers in boxing history.

In 1919, Dempsey decimated Jess Willard inside seven rounds to become the new heavyweight champion of the world. Dempsey is regarded as one of the greatest heavyweights of all-time but his activity as world champion was laughable, competing just five times in five years, and never against a black opponent.

Wills, despite his colour, was widely considered the rightful contender for Dempsey’s crown and, by 1925, even white boxing pundits were beginning to ask what was so wrong with giving the man a shot?

Alas, the fight would never happen leaving one of the biggest ‘What ifs?’ in boxing history. Like a pre-Depression Riddick Bowe vs Lennox Lewis, we’ll never know who'd have come out on top if they fought.

With Wills the clear frontrunner for the Dempsey fight, the New York State Commission even refused to sanction any other championship fight for ‘the Manassa Mauler,’ other than Wills, much to the dismay of Dempsey’s promoter Tex Rickard, clearly not ecstatic about a mixed-race title fight. Ultimately, Dempsey would give up his New York license, opting to defend his title against Gene Tunney in Philadelphia instead.

Out of the window went any chance Wills had of claiming the world title. Fast forward to a little under a century later and Dempsey’s name has been cemented into boxing’s long line of all-time icons, while Wills’ name remains largely forgotten. An absolute injustice.

At the age of 43, he hung up his gloves for good in 1932 and although overlooked by the annals of boxing history, the story of Harry Wills did end on somewhat of a cheery note. In stark contrast to the fates of countless other heavyweight peers of his, in retirement Wills invested his ring earnings wisely, finding great success in the New York real estate business.

On December 21, 1958, Wills died from diabetes, leaving an estate valued at over $100,000 (a fortune at the time), including a 19-family apartment building in upper Harlem.